.svg)

At a time when many households are struggling with the cost of living - and steadily rising energy bills - solar, batteries and electric machines can help reduce costs because they are so much cheaper to run. The issue is that these things are expensive upfront and many of those who would benefit most from the savings don't have access to finance to buy them. That's why offering people a way to pay for these electric upgrades over time is so crucial. And that's what the Ratepayer Assistance Scheme (RAS) offers.

Unlike bank green loans, access to affordable loans could enable household savings immediately because repaying the loan and interest costs on solar, batteries and electric machines over the long run will be lower than the current electricity and fuel costs. In other words, it will be cheaper to finance the new things than to keep paying to run the old things.

We've been working alongside a number of partners to bring Energy IMPACT loans through the RAS to life. These loans would be tied to the property and flexible payment terms would be available.

Rewiring Aotearoa's policy manifesto ranked long-term, low-interest loans for electric upgrades as the most effective option out of 60 ideas. The numbers stack up for households and they also stack up for the country as a whole. We believe this policy has the potential to be the energy equivalent of ACC or Kiwisaver and will reduce the cost of living, slash emissions and increase resilience - all without imposing any debt or risk on councils or the Government.

The RAS could also be a global precedent that other countries could follow and it goes a long way to solving the equity issue of electrification. The business case has been delivered, there is wide support for the idea and, if the Government prioritises it, these loans could be available by next year.

Jump to sections:

- The problem

- The biggest barriers

- The solution

- What about the banks?

- The long and the short of it

- What are the banking barriers?

- Different strokes

- Why solar makes sense

- Customers as energy infrastructure

- Funding resilience

- Emissions decisions

- A bad case of gas

- Strong and stable

- Why has this finance solution taken so long?

- Why should councils care?

- Why is the RAS a better option?

- On balance

There's a lot of reading in this one. Let's show some interest!

TLDR? Check out the infographic

The problem

There is an urgent need to reduce the cost of living for New Zealand households.

In the year to October 2025, electricity prices were up 11.8% and gas up 14.4% [1], with electricity prices expected to increase around 30% before the end of the decade [2].

Even before recent rises, 67% of homeowners were worried about their electricity bills, and 45% were already experiencing significant financial strain[3]. The month to 31 July 2025 saw more than 31,000 customers enquire about payment deferral or flexibility, a 60% jump in a single month and the highest on record by more than 8,000.[4]

The impact is most severe on low-income households, with those in the lowest income decile spending over seven times more of their income on electricity than those in the highest. Consumer NZ estimates that 140,000 households have had to take out loans to cover their electricity costs, and 38,000 households have been disconnected at least once in the past year due to unpaid bills.[5]

These costs aren't just affecting households, they're costing the Government as well. In 2024, over 900,000 households (62% of whom were superannuitants) received the Winter Energy Payment at an annual cost of nearly $527 million. On top of this, the Government provided almost $19 million in hardship grants to help New Zealanders cover their power bills, averaging more than $500 per grant.

Energy hardship also costs the health system tens of millions per year on physical health issues such as asthma, and also increases the risk of severe mental distress.[6] Energy hardship has further wider economic impacts that are difficult to assess.

These numbers show the scale of the problem, and why reducing household energy costs must be a priority.[7]

The biggest barriers

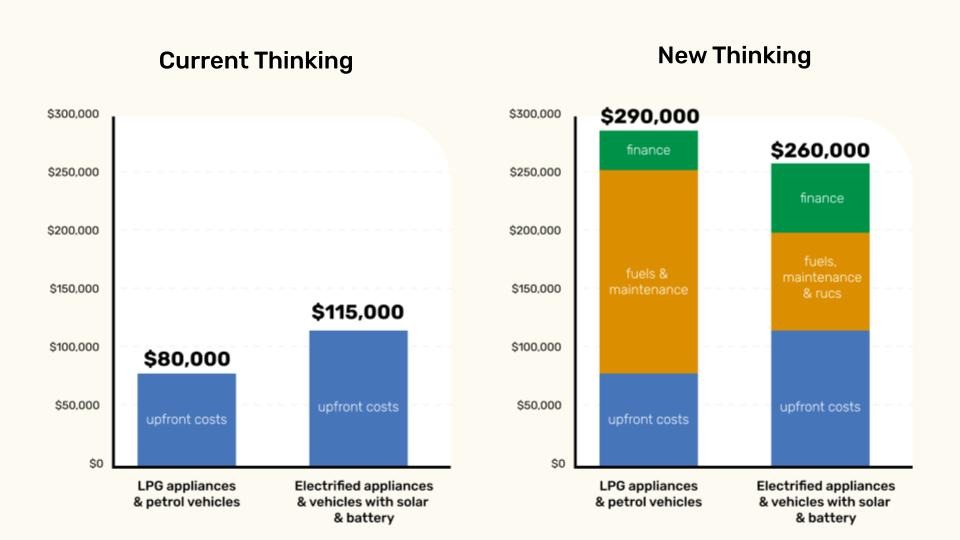

Like most electrified machines, the costs of solar and battery storage are front-loaded: the big cost is at purchase and installation, while the savings roll in year after year. Fossil-fueled machines are the opposite: easy to buy, but can be costly to operate, for example a gas water heater versus an electric heat-pump hot water system.

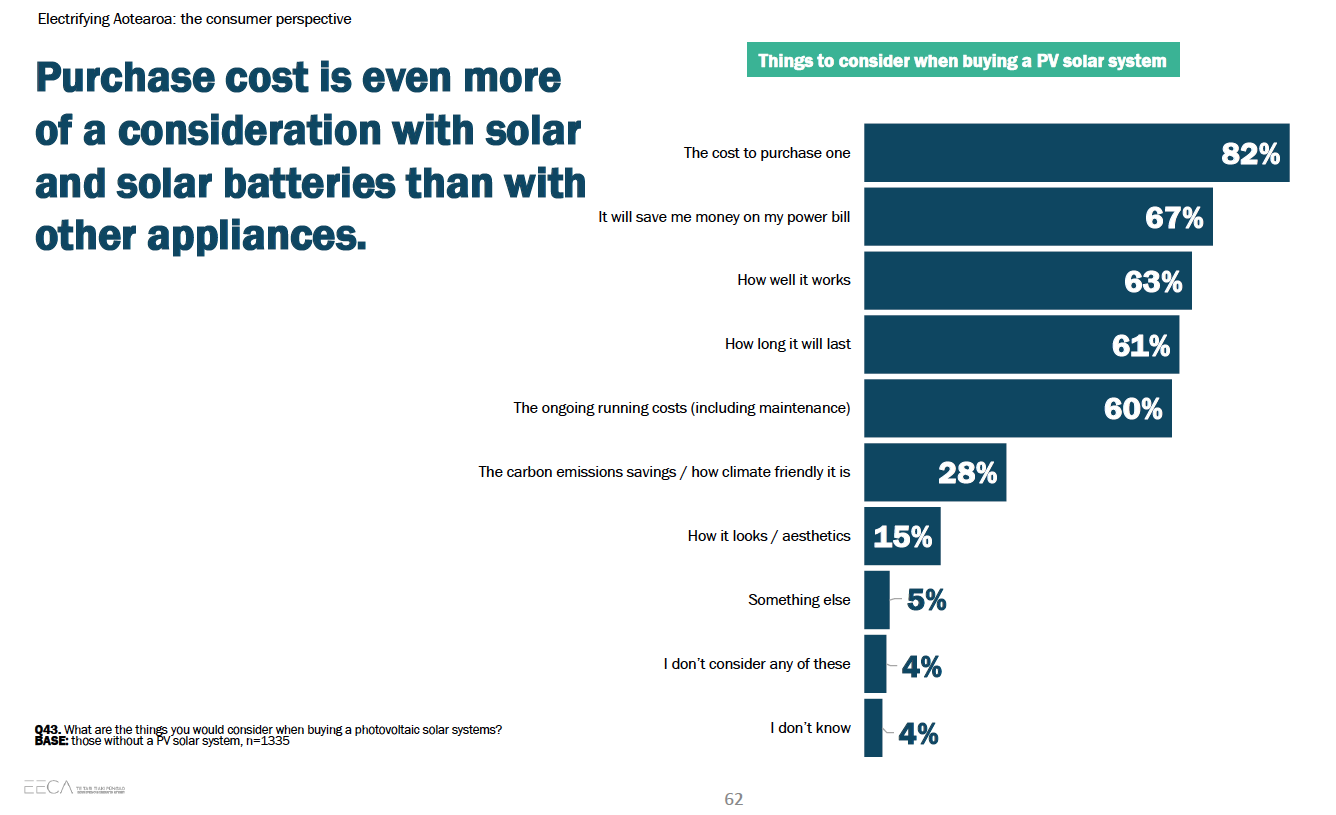

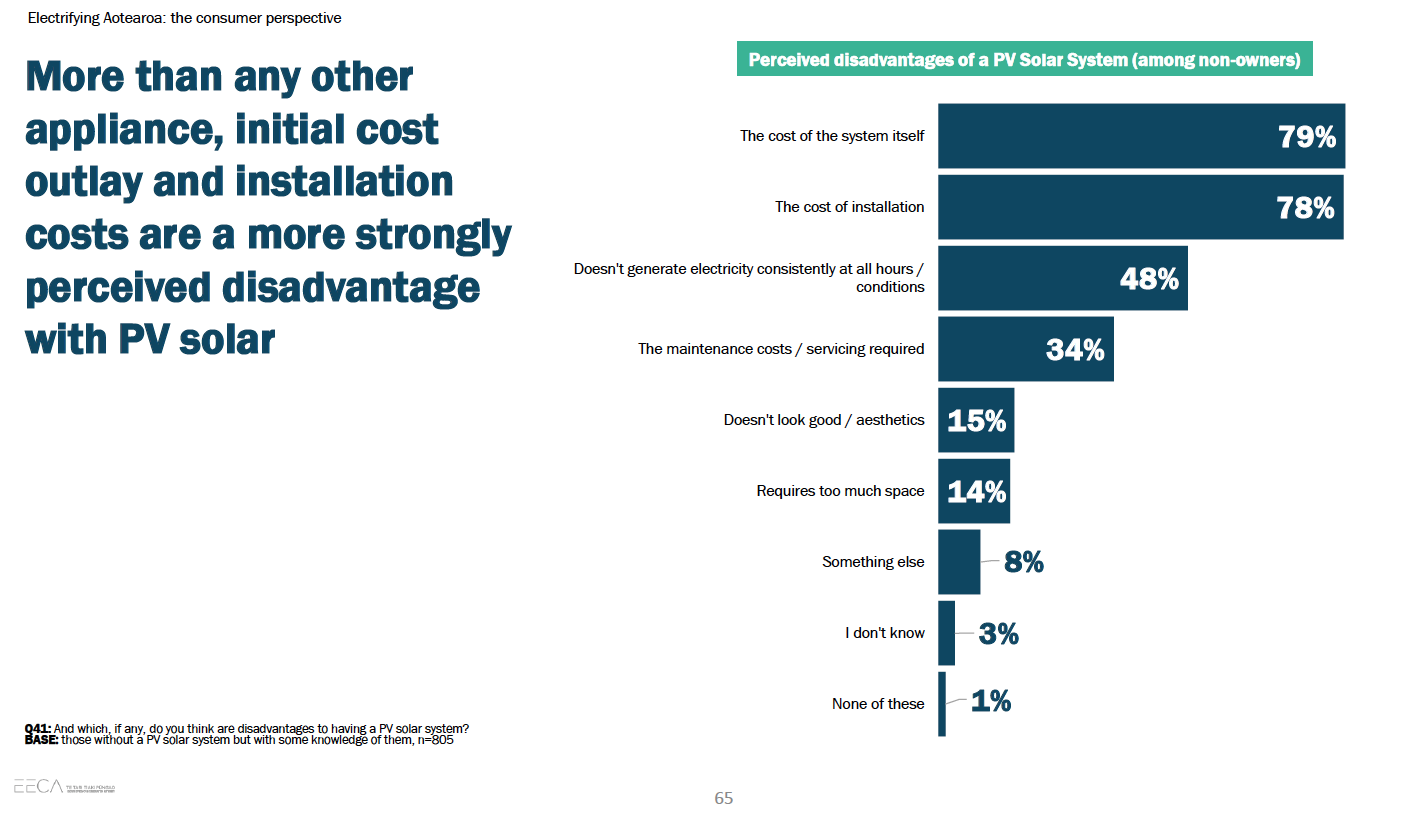

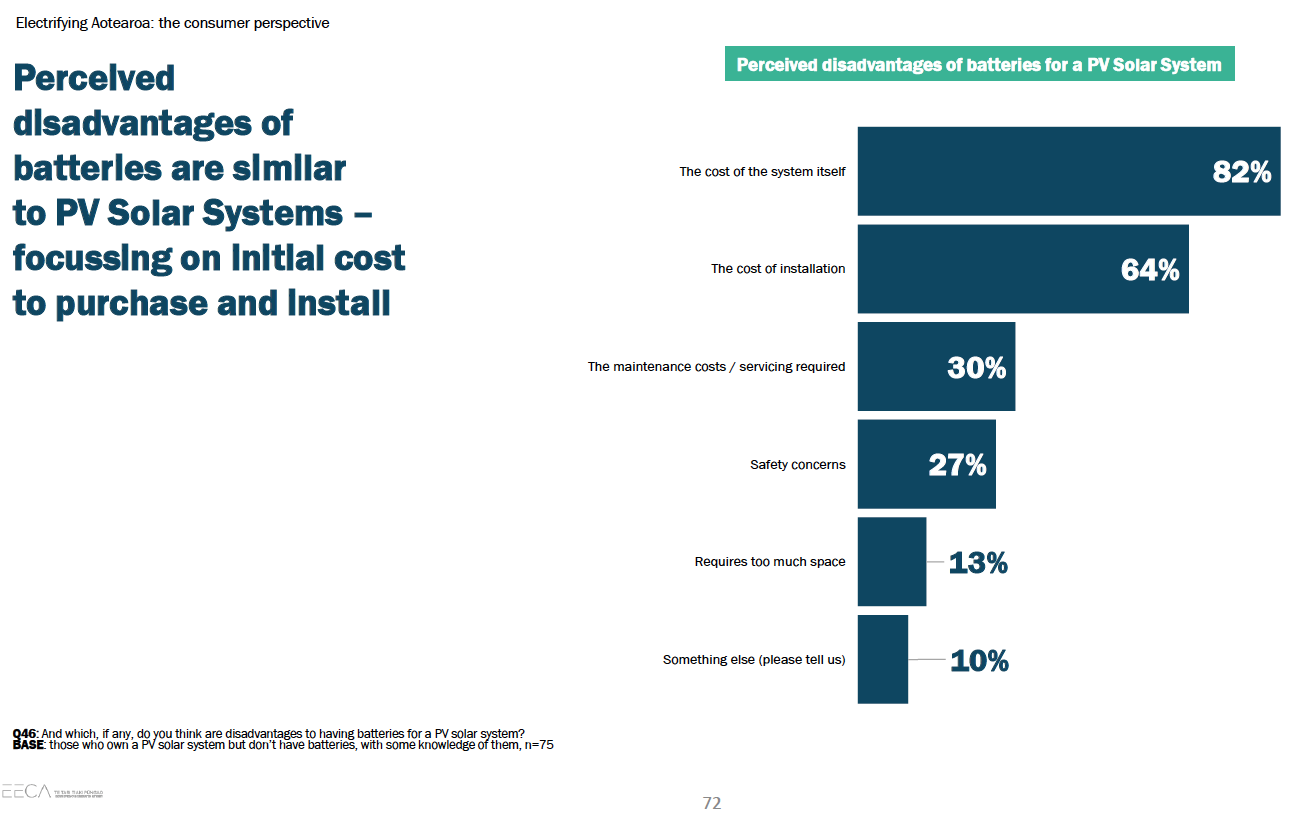

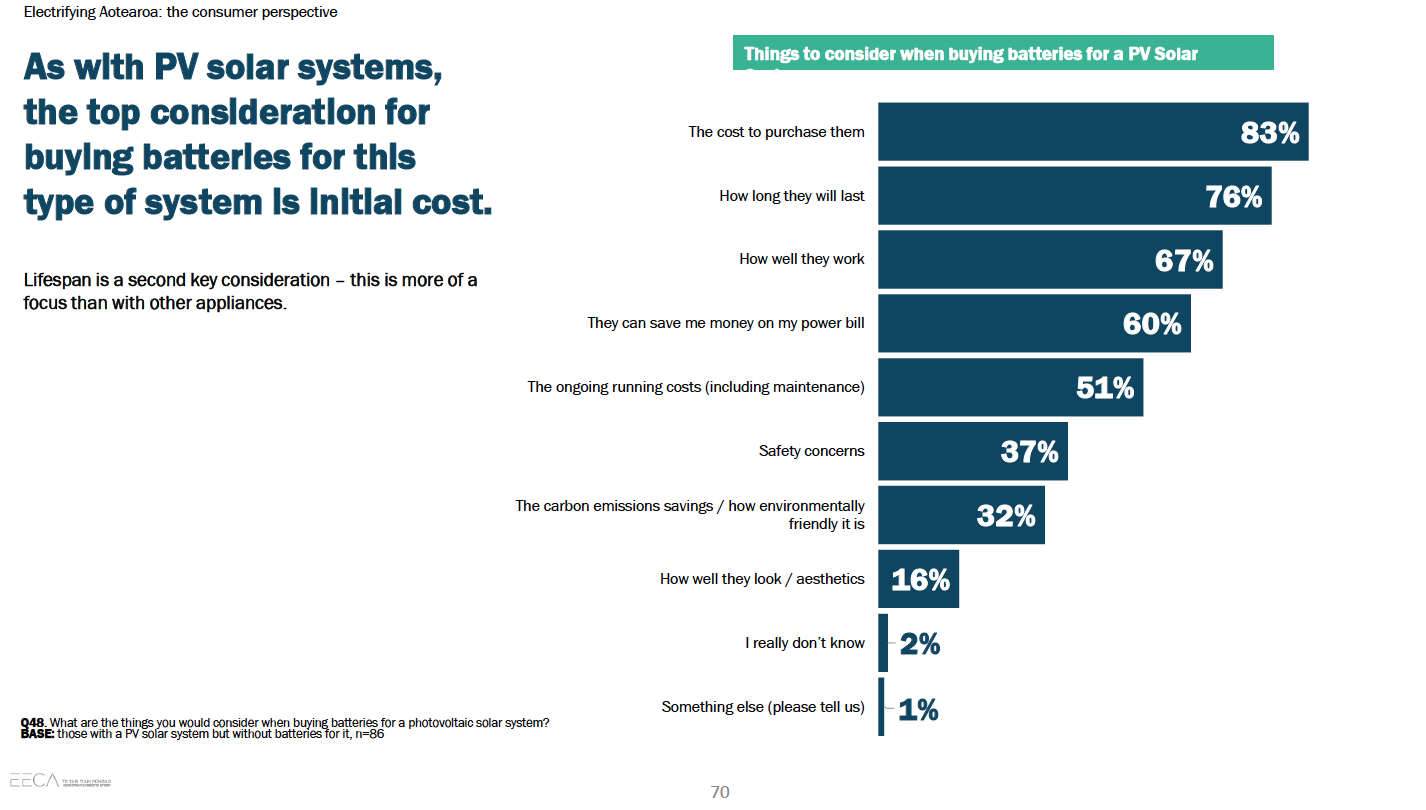

These costs, as shown in the following graphs from EECA research, demonstrate the prominence of upfront costs for solar for consumers:[8]

There is significant untapped demand, with more than three-quarters of households either eager to electrify or indicating latent demand.[9] Upfront capital costs are the biggest barrier to mass solar adoption and electrification. Therefore, access to appropriate and affordable finance is critical.

Having access to accurate, trusted, and accessible information, and making the install process easier will also help. Parallel work to address these barriers is underway across public sector organisations like EECA, NGOs like Rewiring Aotearoa, and private companies/social enterprise collaborations.

Some people have concerns about the perception of taking on more debt to finance upfront costs. These concerns can be allayed if this is reframed as an investment, where one 'energy subscription' is swapped for a cheaper energy subscription - even though it is financed. The overall impact is lower household costs in the short term, bigger long term savings and potentially increased property value.

While the RAS doesn't cover vehicles, the below chart illustrates the thinking.

The solution

The RAS offers affordable, accessible low interest, long-term energy loans to every rateable property in New Zealand with flexible repayment options.

It is expected to offer finance at around 2% below banks' floating mortgage rates (and most often below their 1 or 2 year "specials"). These long term loans will also better match the expected lifetime of these products.

Rewiring Aotearoa, with the support of EECA, has been working alongside the local government sector to develop the scheme. It builds on an established successful model used by councils to access credit via the New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA).

Using the LGFA, councils reduce borrowing costs while providing investors with a stable return on investment. Because the loan is tied to the individual rateable property and no one shareholder owns more than 20%, the debt from these loans will not appear on the books of the councils, or central government.

It will be a national shared service available to all local authorities in New Zealand, removing existing administrative burden and centralising the specialist capabilities required.

It enables billions of private capital from here and overseas to easily flow to deliver public and private outcomes and can efficiently access significant residential property equity (currently ~$1.2 trillion) to achieve public and private benefits.

The RAS keeps rates low and terms long by cutting risk and cost. Government (both central and local) involvement lowers risk, simple approval requirements trim transaction costs, and patient lenders accept longer terms for safe loans.

It also includes additional elements to help older New Zealanders stay in their homes by delaying rates payments and unlocks additional housing development by deferring development contributions.

What about the banks?

Current finance offerings reach some, but leave many behind.[10] They are only available to a subset of mortgage holders and while some new products are likely to emerge, it is unlikely these will be easily accessible to many.

"Adding to their mortgage or an existing loan was unappealing to most, preference was for a discrete loan." EECA research[11]

New Zealand's major banks have "green loans" available for a wide range of upgrades including home energy production and storage, insulation/double glazing, EVs and EV chargers. The current offerings are:

- ANZ Good Energy Home Loan Top-Up: 1% per annum fixed for 3 years, up to $80,000

- Westpac Greater Choices Home Loan: 0% per annum fixed for up to 5 years, up to $50,000[12]

- BNZ Green Home Loan Top-Up: 1% per annum fixed for 3 years, up to $80,000[13]

- ASB Better Homes Top-Up: 1% per annum fixed for 3 years, up to $80,000.[14]

Kiwibank's Sustainable Energy Loan is only for household-scale energy production (solar, hydro, wind or geothermal). It is offered at their standard variable home loan rate for a loan term of seven to ten years, and sees Kiwibank contribute up to $2,000 toward your system if you borrow more than $5,000.[15]

Non-mortgage related personal loans from banks have interest rates generally between 12% and 20%.[16]

Given fluctuations in interest rates since many of these products were first established, we expect banks are losing money on the low or zero interest rate products, which calls into question their long-term viability to fund household solar and electrification. If one bank pulls their low or zero interest rate product, others may follow suit.

For all green loan home loan products, you need to either have an existing home loan with that bank, or shift your home loan to the bank.

Some banks require households to have a minimum loan balance to qualify. For example, to qualify for Westpac's offering you must have (or be approved for) a minimum home loan balance of $150,000.

While some households without a mortgage are able to take out a new mortgage for solar and home electrification upgrades, many are unable due to their limited income.

"People without a mortgage, especially retirees, talk about challenges and frustrations not meeting the requirements for the loan"[17]

The long and the short of it

Solar panels can be expected to last 25-30 years (with many panels warranted for 25 years), inverters for 15+ years, and many other electric machines (including batteries and heat pumps) can be expected to last for 15 or more years.

The promotional low-interest loan terms are much shorter than the expected lifespan of these machines. In the case of Westpac's 0% offering, you need to be able to repay the loan in full within five years. ASB, followed by ANZ and BNZ, have updated their loan offerings and now enable households to amortise the loan over longer total terms than before, with the interest rate often defaulting to the standard bank floating mortgage rate at the end of the low-interest period .

Even when households aren't required by the bank to fully repay the loan in the discounted interest rate time period, many feel pressured to pay off as much as they can during the discounted rate period so that they do not face interest rate increases of 5-6%. In practice this means that a household will tend to increase their energy bills and cost of living when they take out a solar loan through such 'green loan' offerings.

Even if banks were to offer longer-tenor loans in the future, banks typically price mortgage lending for a maximum of five years, and loan pricing would be likely to reprice at this point in time. This leaves households uncertain of future interest costs. While RAS interest rates are likely to be reset quarterly and therefore somewhat uncertain, the difference between 0% or 1% and the bank floating rate is likely to be more noticeable for homeowners than the smaller RAS fluctuations over time.

In most cases, the household will be in a cash-negative position for those three to five years, as the energy savings will not be enough to service and repay the loan. Rather than alleviating cost of living pressures for three to five years, current financing offerings can add to these pressures, meaning that households don't see the benefits of cost savings until the loan is paid off and they own the asset.

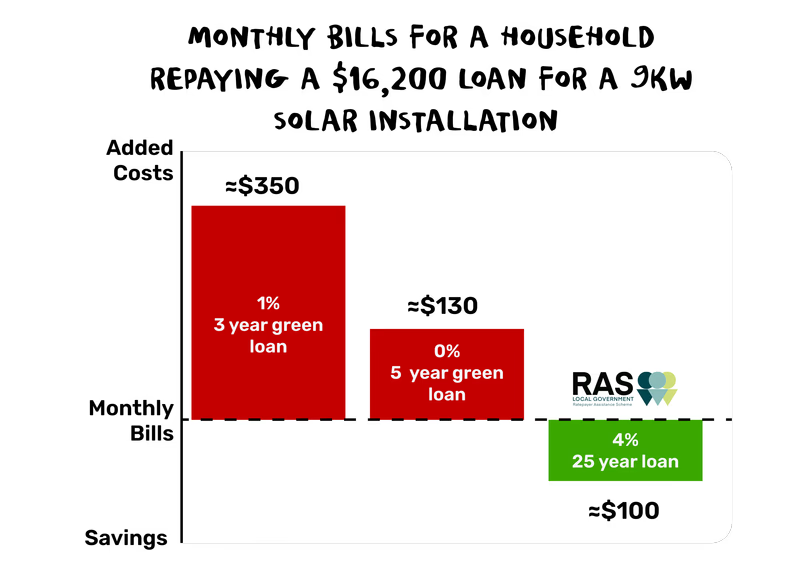

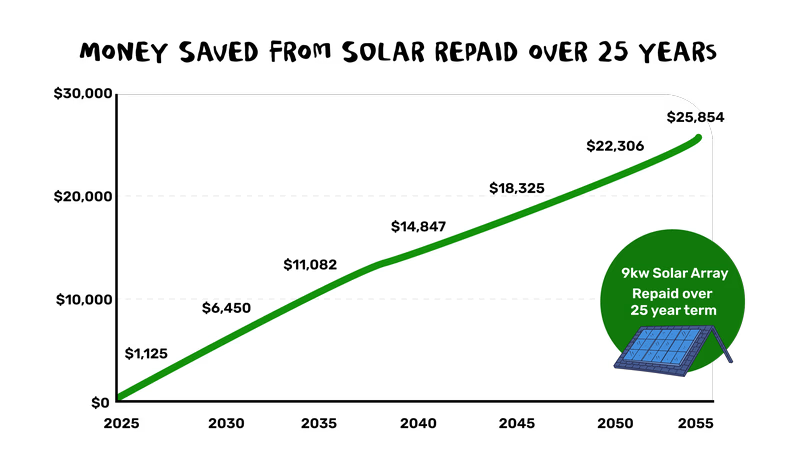

For an average household repaying a $16,200 loan for a 9kW solar installation solar, here's how monthly bills would change under different options while repaying the loan:

- $363 more in monthly bills (including $565/month full loan repayment at 1% if repaid fully over three year promotional period through ANZ, ASB, BNZ)

- $132 more in monthly bills (including $334/month full loan repayment at 0% repaid over five years as required by Westpac)

- $96 less in monthly bills (including $106/month full loan repayment if repaid on the RAS over 25 years at 4%)

New Zealanders need energy bill savings now, not bill increases now in exchange for bill savings in three to five years.

"[Solar] Adoption is easier when financing removes the need for lifestyle sacrifices."[18]

After the initial cost of living hit for three to five years, the households that can afford to pay back loans in a shorter period will have significant monthly savings for the remaining 25-27 anticipated years the solar will produce power. Currently those who can afford to take a short-term "hit" will benefit from significantly lower energy bills for decades to come, while those who can't afford the upfront cost will not. Energy inequality will continue to widen without providing access to long-term finance to those who currently are unable to access it.

What about the banking barriers?

Potential energy bill savings are not considered in loan equations

A green loan application needs to go through a detailed reassessment process for the home, which can not only be mentally fatiguing for households, but can be denied based on current income levels and house valuations. Loans may be denied even if the installation will save more money than it costs, because future energy bill savings are not included as part of assessing affordability criteria. While an energy company building a solar farm would have the future income from Power Purchase Agreements considered by banks, the equivalent for a household (i.e. future energy bill savings) are ignored despite it being largely the same technology.

In addition, applications for home loan top ups can be declined if a home's council or rateable value has not been updated to include improvements. And the value of adding solar panels is not included in these calculations. In these circumstances, households would have to obtain a new valuation (at their cost) in order to prove eligibility for the home loan top up.

The process to get a green loan is often very cumbersome

While installing solar and electrifying can lead to a decrease in monthly costs for a home, banks currently only include the cost side in loan assessments and not the savings unlocked. Banks are operating within their carefully managed operating procedures, designed to meet the many and varied requirements of New Zealand legislation/regulation (such as the CCCFA).

Anecdotally, loan approval bank staff do not consistently understand product eligibility and it can require significant commitment from consumers to get through the process.

"The waiting period for loan approval can cause frustration"

"It can be hard for some to secure financing or a lengthy process with loan applications."[19]

Current products are not widely taken up

Due to high administrative costs and low/negative direct bank earnings from these green loan offerings, banks do not tend to widely push these products on their mortgage holders. ANZ has issued approximately 6,000 green home top-up loans per year the last three years[20] out of their estimated 300,000-400,000 residential mortgages, so around 5% of their mortgages over the three years.[21] This is likely similar to the take up with other banks, meaning it is likely that less than 3% of all New Zealand households have taken out a green home top-up loan.

Some banks may not be able to offer longer-term low-interest green loans

Due to Reserve Bank requirements[22], capitalisation and/or balance sheet constraints, some banks are unlikely able to offer long-term green loans (e.g. 15 year) even if they wanted to.

Different strokes

In general, senior individuals canvassed from some of our large banks do not see energy loans through the RAS as directly competing with their green loan products as they are quite different in structure and target different customers. In fact, several senior individuals see benefits for their bank and Aotearoa in energy/electrification loans through the RAS.

There are a range of benefits that can flow to the banks (and beyond) from energy loans funded through the RAS, including:

- Reduced credit risk from home loans: Increased disposable income to meet mortgage payments for those customers who install solar/electrify

- Cost reductions increase customers they can lend to: once energy cost savings are actually achieved, they can be taken into account in bank affordability calculations, meaning banks can lend more to a larger group of households

- Decreases in banks' Scope 3 emissions

- Local energy resilience benefits

- The macroeconomic benefits to New Zealand of more widespread electrification

- Opportunity to invest (via bonds) in household energy production and electrification for households that are challenging for the bank to otherwise support

- Reducing reliance on loss making products: banks are likely to be making losses on low and zero interest green home loan top ups, providing an alternative source of funding that is more accessible will reduce these losses.

Further work is required to fully understand the impact of the RAS on banks (in particular on mortgages) and, as appropriate, ways to mitigate any negative impacts. Different RAS products may be viewed differently by banks. As banks are best positioned to understand their likely reactions to the RAS, discussions on the RAS are underway with banks.

Why solar makes sense

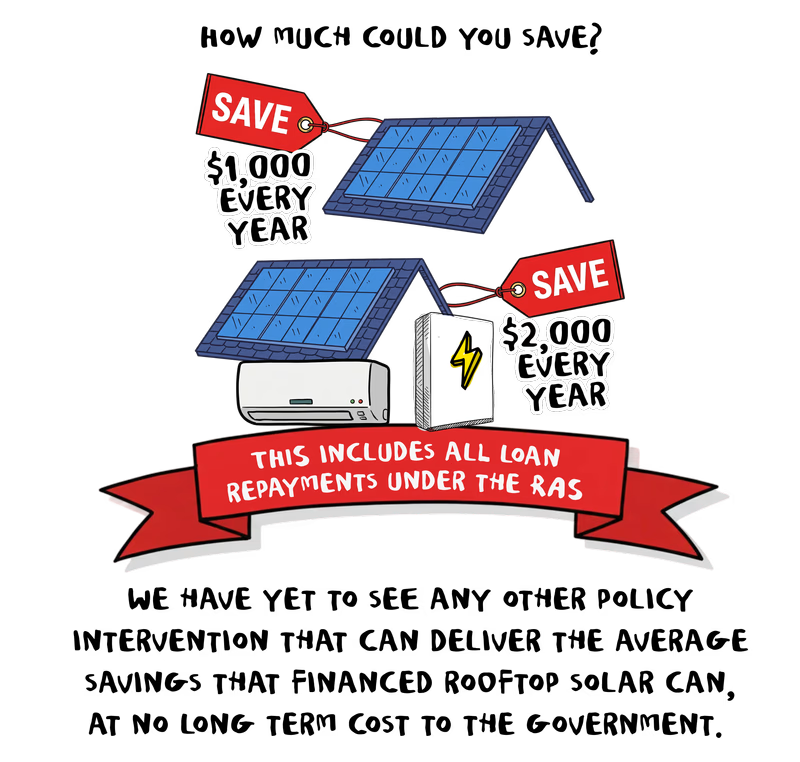

Solar alone can save the average household around $1,000 in the first year if financed on the favourable terms the RAS can make available.[23] This includes repayment costs, with those eligible households such as pensioners who choose to defer repayment until they sell their property unlocking around $1,900 a year in cash to meet wider costs of living.

Rising electricity prices mean that the household savings from solar are likely to increase for a period, which may then fluctuate over time depending on how much households are paid per unit of electricity exported.

Long-term loans for solar will not be appropriate for every household, and the consumer disclosures and protections that are planned to be built into the RAS and delivery of Energy IMPACT Loans are critical. The RAS alone will not ensure every household, such as those that rent, can access the savings from solar. It will, however, broaden access to finance for household solar beyond what is currently available through existing bank products.

In addition, we and others are trialling different approaches to ensure renters can access the benefits of solar and electrification and are not left behind.

We have yet to see any other policy intervention that can deliver the average savings to households of $1,000 per year that financed rooftop solar can, at no long term cost to the government.

A lot of a little is a lot. If 10% of homes - around 200,000 - had solar and battery storage exporting to the grid, this would equal the peak response of the Huntly power station.

This can be done. Australia is currently installing over 1,000 household batteries a day as part of a subsidy programme[24], and nearly 40% of homes have solar. Even at our currently low installation of residential batteries, by 2030 there would be 280MW of residential batteries, the ninth largest power station in the country.

Household, farm and business solar and batteries therefore can have a positive impact not just on the individuals that own them, but on the overall system through increased supply and reduction in peak. This lowers network costs, which end up on customers' bills and are expected to make up the biggest increases in the coming years.

As the energy transition requires significantly more electricity (the Government's Electrify NZ features the goal of doubling the supply of renewable energy, but many think we may need more than that), it is clear households and farms can play a significant role. These individual solar and battery systems can also be deployed significantly quicker than large-scale generation alternatives.

Dry and sunny

In addition to playing a significant role in generally meeting future demand, household and farm solar can make a meaningful difference with our dry year hydro challenge. In a dry year, there is an estimated 11% bonus in solar production in the important late summer and early autumn period when it isn't raining. This equates to 225GWh of extra production in a dry year if a 9kW system was installed on 50% of homes. This 225GWh is 5% of New Zealand's total hydro storage capacity.

If it had been there in 2024, it would have been an extra 18 days of storage, based on the trajectory of national storage in July/August. Five percent or 18 days may not sound like much, but when storage bottomed out in 2024, all else being equal this would have more than halved the wholesale price at the worst time of the crisis, lessening the crippling impact on many industries of such wholesale price spikes.[25]

Customers as energy infrastructure

Growing demand for electricity puts further strain on transmission and distribution lines and some local networks, which are already nearing capacity, especially during peak times. Transpower and electricity distribution companies (EDBs) continue to actively plan and obtain permission to fund line upgrades. The largest likely rises in consumer bills over the coming decades are expected to come from upgrades to distribution infrastructure. Boston Consulting Group estimates these costs to be $65 billion over 25 years.[26]

However, household batteries and solar offer an alternative that can in many instances deliver the same outcome at much lower cost.

When a battery is installed, it removes the household or business from peak. This effectively enables more electricity to run on the same network assets and more households to be served by them. The addition of battery storage can therefore delay or prevent the need for expensive grid upgrades and enable us to get more out of our existing assets.

Household solar enables more energy generation into the energy system. This reduces the need for additional generation to be built and grid infrastructure to deliver that energy over long distances, therefore lowering future system costs.

Because solar and battery adoption happens household by household, the real question is timing: will enough homes add solar and storage before network companies commit to building costly new grid assets?

If the adoption can be encouraged to happen earlier, it could save billions in energy infrastructure investment. A more flexible electricity system, including many more household batteries, could save New Zealand up to $10 billion by 2050 and keep power bills lower by as much as 50%.[27] These savings are for every household on the network, in addition to the specific savings for households that install solar/batteries.

Work in Queenstown examining how to meet future energy demand and increase resilience has compared the opportunities for solar and batteries to delay or displace the need for a second transmission line, which could cost an estimated $720 per annum per household. Rewiring's analysis suggests such a deferral could save the community tens of millions of dollars.

A recent report[28] showed that if 6,000 Queenstown homes (around a third of existing homes) installed 5 kW of solar and 25 kWh of battery storage, it would be enough to meet peak winter demand even for extended periods of cloudiness. It would also defer the need for a new line by 2-4 years, and that deferral of 3-7 years is possible with solar, batteries and demand flexibility in a high demand growth scenario and more than 7 years in a non-high growth scenario.

Another recent report[29] found that even if less than 7% of new household builds around 2033 had a 7 kW solar system and 10 kWh battery, this would be enough to provide energy security for a 24-hour period during peak winter demand, and 80% of new builds around 2050 would be enough to provide 8 hours of such energy security. Adding solar and batteries to existing housing stock, as is already happening in Queenstown, reinforces that significant delay or even displacement of investment in lines and grid infrastructure may be possible (and economically beneficial for the households that install, alongside benefits for all households).

Installation of solar and electrification of our households requires skilled professionals. While certain parts of installations are limited to electricians, there are also opportunities for roofers and general builders to take on significant amounts of solar installations. Additionally, every million dollars spent in New Zealand on electrification rather than overseas on coal could create around eight jobs, with that extra 600,000 tonnes of coal imported equating to around 1,000 jobs for one year if the money had been spent domestically.[30]

Funding resilience

Following events like Cyclone Gabrielle[31] households with solar power and batteries were able to continue to operate as usual and also provide vital services to their communities – like cooling, cooking, charging and communication.[32] As noted in the draft DPMC and MfE Long-Term Insights Briefing[33], we can expect events of this severity more often.

This resilience provides critical services in times of crisis. This enables food to be kept chilled/frozen and cooked, communication and, importantly, reduces the demand on emergency and medical services to support households that are medically dependent on electricity (such as for home dialysis and breathing support). This is important, as nearly 10% of all residential connections are registered as medically dependent on electricity.

If homes own electric vehicles, it will allow them to travel for extended periods of time while the network is out, and provide a crucial transport lifeline if fuel deliveries are cut off. For example, an Alpine Fault 8 event in Queenstown could cut the town off from petrol/diesel supply by road for several weeks or months. In these situations, electric vehicles could recharge from household / local solar generation and provide vital transport and access to households and communities.

We have also recently seen the benefits for rural resilience. Some farms with solar and storage in Southland were able to continue milking and keep that milk cold during the October weather event.[34] Such farmers were also able to offer their neighbours hot showers and fresh food.

Emissions decisions

Emissions from energy decisions made by households account for approximately 15% of New Zealand's total emissions, or around 31% when excluding those emissions embedded in exports.[35] New Zealand is on track to face a $3–$24 billion cost from having to buy international carbon credits to meet our 2030 Paris targets. Over 25% of our gross carbon emissions come from small fossil fuel machines, which can be replaced by existing technology today. If all homes electrified all their fossil fuel machines by 2040, around 10 million tonnes of emissions would be saved annually (105 million tonnes saved cumulatively between 2024 and 2040).

The more homes that install solar, the greater still the emissions savings. With the recent deal to add an extra 600,000 tonnes of coal to the stockpile at Huntly Power Station, the total will reach 1.1 million tonnes, or about 110 days of running all units at Huntly.[36] Avoiding burning those 1.1 million tonnes of coal can avoid 2.75 million tonnes of emissions. While another dry year will mean that is not possible, every household with solar means we are burning less coal, with the average home with solar's 23kWh production for in winter the equivalent of 13 kg of coal, or around a tonne of coal every 77 days per home with solar.

The International Energy Agency recently found that one large container ship full of solar panels "can provide the means to generate as much electricity as… the coal on over 100 large ships". With around 200,000 tonnes of coal on a large coal ship, if five similar sized ships were used to deliver solar panels instead of the coal for the stockpile, it would deliver many, many decades more electricity.

A bad case of gas

As the supply of gas continues to diminish, gas prices will increase and push even more households into energy hardship. The upfront cost of switching from gas to electricity will be a barrier to some households, risking them being locked in to ever-increasing gas prices. Finance can support households to switch off gas when they consider the time is right.

An abundance of solar, alongside different management of our hydro assets, can additionally reduce the need to burn gas for firming of our electricity supply, and free up gas for industries that do not yet have viable economic alternatives.

Recent modelling from the New Zealand Green Building Council found "replacing gas and inefficient electric heaters with heat pumps could save up to 48 Petajoules of gas annually - nearly 40% of current production - and deliver net electricity savings of up to 4,000 GWh per year, enough to power over half a million homes. It'd also save New Zealand households up to $1.5 billion a year on energy bills."[37] While these savings figures are based on the conversion of more than just residential heating and may overstate the percentage of current gas production that could be freed up, they point generally towards what is possible.

Strong and stable

Significant take-up of rooftop solar and batteries is likely to be both anti-inflationary, and bring incredible price stability to households. Operational household energy costs for the expected 30-year life of solar panels will not only be significantly lower, but also entirely stable because with solar, households will be locking in the price of that energy for 30-plus years.

While there could be some short-term minor inflation driven by labour bottlenecks and rollout logistics, the solar installation industry can be expected to quickly scale and increase efficiencies, as was seen in Australia. As some of the required labour (roofers and builders in particular) is currently facing relatively weak demand, this may not eventuate.

In addition, increasing uptake of solar, and electrification of machines, reduces our reliance on imported liquid fuels, and improves our balance of trade. This allows cashflow to be retained in New Zealand, and has flow on effects like a stronger New Zealand dollar, which can help households with inflationary pressures by making imports cheaper.

Why has this finance solution taken so long?

There are a range of market failures with respect to household energy resources in New Zealand's electricity market, the wider energy market, and the finance and capital markets. These warrant Government intervention, including supporting Energy IMPACT Loans through the RAS.

The biggest of all market failures is that current markets (finance and others) do not reflect the significant positive externalities (in economist speak) of electrification and solar, with no incentive for banks or big energy players to change this. In non-economist speak, banks and energy providers don't adequately reflect the wider public benefits of household electrification in their offerings. These benefits include important things such as additional electricity generation delivered quickly (reducing the urgent need for new large-scale generation investment and lowering wholesale prices), lower grid infrastructure investment required (reducing costs for all electricity users), improved household and community energy resilience, support with diminishing gas supplies, enhanced energy and fuel security, reduced emissions and related liabilities, and much more.

As outlined earlier, solar, batteries and electrification is economically efficient. However, access to electrification is being blocked by inefficient access to capital. Further, this delayed uptake, caused by capital access issues, may end up costing consumers billions of dollars in unnecessary network investment.

Due to the scale and long-standing and stable perceptions of large-scale energy generation and distribution, big firms and organisations (like Transpower) can access long-term and relatively affordable finance through capital markets.

For the same underlying investment (e.g. solar energy production, distribution network services), households are unable to access such long-term finance. Household demand for long-term finance is not met, despite the broad social benefits that would be delivered.

This is due in part to:

- High transactions costs as it is more expensive to underwrite hundreds or thousands of small loans compared to one large loan, and more difficult to undertake hundreds or thousands of household energy calculations (which would show in most cases repayment capacity is very strong over time and often better than utility scale) compared to a single energy production calculation; this means the energy economics that would be undertaken if loaning money to an energy company to build a solar farm are ignored when a household invests in the same technology

- A household's inevitable need to consume electricity is not recognised as an equivalent to a long-term power purchase agreement[38] for the solar installation. Indeed, while commercial power purchase agreements will have limited terms (e.g., 10 years), a rooftop solar installation arguably has a guaranteed purchaser for the life of the installation

- Households may not have the financial literacy or confidence that generation and distribution firms/organisations have.

There are institutional investors who would like to invest in long-term stable products to support household energy production and storage, but no existing mechanism for them to do so.[39]

The Government has actions underway to further facilitate the easy capital flows required for large private infrastructure, such as through InvestNZ (complementary to the National Infrastructure Funding and Financing agency that is aimed at public infrastructure projects). Such initiatives will play an important role in addressing our infrastructure deficit, but in isolation, improving access to finance for households will further the divide between small-scale infrastructure investment and large-scale.

Both are required to improve our energy productivity and resilience, and the RAS can play a role in enabling smaller-scale investment through provision of more affordable long-term capital.

Lines companies (EDBs) and Transpower, considered natural monopolies, currently receive guaranteed returns on capital expenditure through price-quality regulation. Consumer energy resources (e.g. solar and batteries) are able to provide some of the same services to communities, and at times are more resilient than what is provided by EDBs and Transpower. However, there is no guaranteed return on investment for consumers who invest, meaning the regulatory framework implicitly biases/subsidises centralised network infrastructure over consumer energy resources.

Put another way, the regulatory environment for our energy and finance systems has not kept pace with the pace of technology. While regulators guarantee the returns on investment for energy companies, everyday New Zealanders are left with no guarantee when they invest in energy assets that can achieve the same results.

This exacerbates the capital market imperfection, as without the security of regulated monopolies, the risks for households are perceived to be higher and contribute to higher interest rates.

Why should councils care?

Councils have the ability to offer home energy loans via voluntary targeted rates (VTRs). But the RAS is less risky, less expensive and expected to be more impactful. Most councils are unlikely to restart their own loan schemes.

Under the Local Government (Rating) Act 2002, councils can set VTRs, whereby a property owner opts into having a charge placed on their property via a targeted rate. This rate is attached to the property, not the borrower. Like all council rates, VTR schemes sit superior to bank mortgages on a property.

Voluntary targeted rates were historically directed towards enabling more warmer and drier homes to improve health outcomes.

Analysis of a selection of 20 councils demonstrates home energy loans align very strongly with council goals, strategies and plans.

New Plymouth District Council considers VTR schemes "a key mechanism to enable support for a variety of sustainability initiatives at the individual home level at no cost to the general ratepayer. Additionally, [a previous voluntary targeted rates] scheme has been proven to achieve significant social and economic benefit for the community, and can help ratepayers to reduce energy costs."[40]

VTR Schemes can deliver significant benefits beyond individual households: better health outcomes, household and community resilience, improved environmental quality and reduced emissions, and more. In improving cost of living for communities, providing more affordable energy and boosting demand for skilled labour, VTR Schemes also have the potential to assist with regional economic development.

Property improvement loans through the RAS align with the proposed new purpose of local government in the following ways:

- "(b) to meet the current and future needs of communities for good-quality local infrastructure, local public services, and performance of regulatory functions in a way that is most cost-effective for households and businesses"

- PILs can help the current community needs to achieve cost-effective running of their home

- PILs are a local public service to provide cost-effective solutions

- PILs can also support local infrastructure, for instance water and wastewater connections, particularly to reduce capital and operating costs such as deferring investment

- PILs can also support regulatory functions, for instance air quality, by providing finance for heat pumps as an alternative to coal and wood burners.

- "(c) to support local economic growth and development by fulfilling the purpose set out in paragraph (b)"

- PILs can provide a means for communities to access affordable finance so that local businesses can install products.

- PILs has the potential to stimulate significant demand for local retailers and trades for approved PILs products, with associated economic growth and job creation.

Up until 2020/2021, over a dozen councils offered VTR schemes for improvements such as insulation and clean heating, loaning out millions to households in their communities. In addition to supporting their communities to have healthier homes and better air quality, some councils also offered VTR schemes to support progress towards council climate action plans and targets. Some of these schemes were offered by regional and unitary councils, meaning the population able to access loans was significant.

Following work by the Commerce Commission highlighting potential breaches[41] of the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act 2003, councils paused their VTR Schemes in 2020-2021. In 2024 VTR Schemes were exempted from the provisions of the CCCFA that they had fallen afoul of[42]. However, councils have been hesitant in restarting the schemes given their experience and perceived risks beyond just CCCFA compliance.

For example, councils are not staffed to be banks, and carry significant risks with VTR schemes. In the case of Auckland Council, approximately $10 million in refunds were provided to over 20,000 borrowers as it recognised there were errors in how it had been calculating interest. There is understandable caution among councils around what regulatory requirements may be hidden within VTR schemes.

Why is the RAS a better option?

The more successful VTR schemes are, the more debt shows on council balance sheets, meaning councils face conflicting incentives around actively encouraging loan uptake, offering high loan maximums and longer loan terms. The RAS would not face these conflicting incentives.

In the recent example of NPDC's work to restart a VTR scheme, the loan term was "a single term of five years reducing Council's risk exposure to interest rate fluctuations"[43], the expected interest rate was above bank mortgage rates and a $15,000 maximum proposed loan amount (i.e. not enough for most solar plus battery installations).

The structure of the RAS enables it to offer long-term loans (25-30 years are possible) with higher maximum loan limits and significantly lower interest rates. All of which does not affect a council's debt limits.

In considering restarting their VTR scheme, New Plymouth district council identified three key risks, all of which are addressed through the RAS:

Changes in law that we are not looking out for as we are not a commercial lending institution… High interest rate leading to low uptake, resulting in increasing the interest rate to recover costs and then spiralling down… Operational risks (e.g. eligibility, supplier disputes…)[44]

It is envisioned that "implementation partners" will be involved in Energy IMPACT Loans and other property improvement loans through the RAS. These partners, for example EECA, will handle the customer journey as well as product and installer accreditation, taking these tasks and associated risks away from local authorities.

The RAS will therefore require minimal administrative support within councils, and will build a centre of financing expertise (to avoid the experience of Auckland and their need to refund millions in miscalculated interest payments). It will also be clear that councils hold no liability for poor installations.

A centralised, national implementation partner such as EECA also brings significant efficiency benefits relative to council-by-council VTR schemes. For example, EECA's role supporting historic council VTR schemes was able to undertake quality assurance for installs in the eight participating councils for around the same amount that a single, relatively small, council spent on quality assurance for just the installs in their area.[45]

While councils have, and will continue to have, the ability to offer home energy loans by standing up VTR schemes, home energy loans through the RAS are almost certain to have higher uptake, larger impact, be more affordable for ratepayers and councils, and less risky for councils than voluntary targeted rates schemes.

Additionally, the RAS offers shareholding councils a modest return on investment (though RAS shareholders may decide to reinvest this return into lower interest rates).

On balance

The RAS delivers a range of benefits.

Big savings for households: Adding solar, batteries and electric machines means almost all New Zealanders could save money from day one. The average household installing a decent size solar system can save around $1,000 a year, and well in excess of $2,000 a year with solar, batteries and heat pumps to heat rooms and water. This includes all loan repayment and financing costs under the RAS.

Lower power bills for all: In addition to saving money for the household, EECA estimates that the 41,700 batteries installed under the RAS (which is a very conservative figure) are expected to deliver around $50 million in the first 15 years in grid benefits nationally by reducing peak electricity demand and the need for costly grid upgrades. These upgrades are set to make up the bulk of energy bill increases in the coming years.

More energy for New Zealand: 80% of households and all farms with solar would double our current generation, with the RAS key in unlocking this. In Australia, the rate of battery installs has been more than 1,000 per day after subsidies were announced and the RAS can help New Zealand start on that journey.

EECA estimates more than half of the energy generated by rooftop solar is likely to flow beyond the house, which reduces the need for large-scale investment in poles and wires. This will also reduce pressure on New Zealand's industrial sector, which is being undermined by rising electricity prices.

Enhanced energy security and resilience: New Zealand is very reliant on imported fuels and therefore vulnerable to shocks and price volatility. At a time when storms are increasing in intensity and frequency, more solar and batteries funded through the RAS will also create a stronger energy system and allow our communities to cope better after emergencies.

Improved energy productivity: EECA estimates that by swapping 40,000 gas hot water heaters to hot water heat pumps, more than 850 Gigawatts of energy would be saved in the first 15 years, with associated cost savings of around $50 million (as a comparison, the Manapōuri hydro power station has a maximum continuous generating capacity of 0.85 GW and it generates enough electricity to power around 620,000 homes).

Sustainability: upgrading fossil fuel machines to electric equivalents will greatly improve outdoor air quality and significantly reduce carbon emissions.

Unlocking accessible and affordable finance can help New Zealanders and help New Zealand as a whole. And the way it's been designed keeps interest rates low and removes risks for councils and the Government.

- https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/360888332/milk-and-cheese-prices-soar-power-prices-continue-climb

- Due largely to approved capital spend on distribution network infrastructure through DPP4.

- https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/energy-poverty-lowest-income-households-pay-more-aotearoa

- https://www.emi.ea.govt.nz/Retail/Reports/G2NODP?DateFrom=20221001&DateTo=20250731&Question=B&rsdr=ALL&si=V3

- https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/energy-poverty-lowest-income-households-pay-more-aotearoa

- https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/energy-poverty-lowest-income-households-pay-more-aotearoa

- https://www.phcc.org.nz/briefing/energy-poverty-lowest-income-households-pay-more-aotearoa

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/insights/eeca-insights/electrifying-aotearoa-the-consumer-perspective/

- https://www.rewiring.nz/news/residential-and-rural-electrification-latent-demand-plenty-of-barriers-and-a-need-for-finance

- This is not intended as a criticism of the banks, who do, should and will play a critical role in the energy and climate transitions. Rewiring Aotearoa will continue to work with banks, and lobby the Government for changes to banking settings to enable banks to develop and offer better energy or climate finance products.

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/assets/EECA-Resources/residential-solar-in-new-zealand-understanding-the-customer-journey.pdf

- https://www.westpac.co.nz/home-loans-mortgages/options/greater-choices-home-loan/

- https://www.bnz.co.nz/personal-banking/home-loans/manage-your-loan/top-ups/green-home-loan-top-ups

- https://www.asb.co.nz/home-loans-mortgages/better-homes-top-up.html

- https://www.kiwibank.co.nz/personal-banking/home-loans/getting-a-home-loan/sustainable-energy-loan/

- As at August 2025.

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/insights/eeca-insights/residential-solar-in-new-zealand-the-customer-journey/

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/insights/eeca-insights/residential-solar-in-new-zealand-the-customer-journey/

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/insights/eeca-insights/residential-solar-in-new-zealand-the-customer-journey/

- https://newsroom.co.nz/2025/08/28/nzers-borrow-over-1b-in-green-loans-for-heat-pumps-and-electric-cars/

- Based on the approximate 30 percent value of mortgages ANZ holds, https://www.anz.com/content/dam/anzco/debtinvestors/fy24-anz-debt-investor-presentation.pdf multiplied by the approximately 1.17 million households with mortgages in NZ per https://www.oneroof.co.nz/news/nzs-mortgage-free-hot-spots-where-homeowners-are-breaking-free-of-debt-46758

- The Reserve Bank applies risk weightings, the riskier the loan, the more capital the bank must hold in reserve. Longer loans have a higher risk weighting, lending over a longer period gives more time for something to go wrong and because the bank has more of its capital tied up over a longer period. This makes long term, low interest loans less attractive for banks compared to short term lending.

- These are based on a 9 kW solar install at $1,700 per kW (plus a replacement inverter at $2,500) on a 25 year term at 4 percent interest, 10 kWh battery at $900 per kWh on a 15 year term at 4 percent interest. All assumptions and full model can be shared. Also note the savings increase even in nominal terms each year, as grid electricity prices increase, this assumes households are not earning much from export revenue.

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/jul/23/australias-surge-in-household-battery-installations-is-off-the-charts-as-government-subsidy-program-powers-up

- https://www.rewiring.nz/watt-now/why-solar-makes-sense/

- https://web-assets.bcg.com/b3/79/19665b7f40c8ba52d5b372cf7e6c/the-future-is-electric-full-report-october-2022.pdf

- https://www.eeca.govt.nz/about/news-and-corporate/news/eeca-and-counties-energy-scale-demand-flexibility-with-karaka-harbourside-dso-pilot

- https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6823b5c571f3675c9ee74139/t/68ba1c09536f135176c88f4/1757027337811/250901+Frankton+final+report+and+results+10+final.pdf

- Note this was not a full technical report exploring full historical records of cloudy days and has limits.

- Job creation numbers are estimated using 8.15 jobs per $1 million of spending on electrification (6.01 direct and 2.14 indirect). These are based on StatsNZ input output tables and Insight Economics employment multipliers. This also draws on Rewiring Aotearoa’s Electric Homes methodology. Assumes a base cost of US$125 per tonne of coal and NZD to USD of 1.7 to reach around NZ$130 million. With import and transport overheads this could be closer to NZ$160 million.

- https://www.seanz.org.nz/resilience-in-wake-of-gabrielle

- Solar alone, with the right technical specifications, offers benefits during daylight hours while batteries extend these benefits.

- https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/risk-and-resilience/building-resilience-hazards-long-term-insights-briefing

- https://www.farmersweekly.co.nz/technology/solar-kept-milk-flowing-in-southland-blackout/

- EECA and Rewiring Aotearoa, based on 2021 emissions data, https://www.eeca.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Electric-Homes-Technical-Report_March-2024.pdf

- https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/business/568921/gentailers-agree-to-stockpile-coal-at-huntly-power-station

- https://nzgabc.org.nz/news-and-media/new-report-heat-pumps-could-cut-household-energy-bills-by-1.5bn-per-year-help-protect-thousands-of-kiwi-jobs

- A power purchase agreement (PPA) is a long term contract between an electricity generator and consumer, such as a large corporate electricity consumer. PPAs provide revenue certainty for generators and help secure attractive debt financing.

- Based on various conversations throughout 2024 and 2025 with institutions including KiwiSaver providers and banks.

- https://www.npdc.govt.nz/media/uewd1qqe/ecm_9522106_v1_workshop-ratepayer-assistance-scheme-whare-ora-loans.pdf

- https://comcom.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/236686/Warning-letter-to-Auckland-Council-23-February-2021.pdf

- https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/27268-fit-for-purpose-regulation-of-consumer-credit-proactiverelease-pdf

- https://hdp-au-prod-app-npdc-haveyoursay-files.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2517/4304/0282/Whare_ora_Loan_Scheme_Report_to_Council.pdf

- https://www.npdc.govt.nz/media/uewd1qqe/ecm_9522106_v1_workshop-ratepayer-assistance-scheme-whare-ora-loans.pdf

- https://infocouncil.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/Open/2019/08/ENV_20190813_AGN_6853_AT_files/ENV_20190813_AGN_6853_AT_Attachment_69515_2.PDF