.svg)

A bad case of gas

We need gas in the short term to generate electricity and for certain industries to keep operating, but gas is expensive, it is likely to get more expensive, and it is running out faster than expected. So how do we use it now? How are shortages and price rises impacting homes and businesses? And what can we replace it with?

New Zealand's gas situation has been all over the news recently: domestic gas supplies are a lot lower than estimates suggested; big industrial gas users, commercial operations, schools and councils are struggling with increasing prices and having to limit operations, shut down or pass increases on to consumers; and residential customers are being faced with higher bills and daily charges for hot water, heating and cooking, limited (or no) options to change suppliers, large fees to disconnect, and the looming prospect of networks shutting down and huge costs being unfairly placed on them. So what’s happening? Why are we in this mess? And how do we get out of it?

Jump to sections:

- The basics

- What's been happening recently?

- Will we find any more gas?

- What has all this uncertainty meant for big businesses?

- What's happening with homes and small businesses?

- Why focus on getting smaller users off gas?

- So, what could replace gas for electricity generation?

- What about batteries?

- Can’t we use bio-gas or hydrogen instead?

- What about emissions?

- What does the future look like?

- What about all the jobs in the gas industry?

- So, what’s the best way forward?

TLDR? Check out the full infographic here.

Let’s light a match.

The basics

Out of the total energy consumed in New Zealand, around 15% came from natural gas in 2024, so it’s an important part of our energy system.

Most of the gas wells in New Zealand are onshore or offshore in Taranaki and they supply our domestic demand, from big companies to small cooktops.

The gas is sent from the wells to a processing plant, before heading through 2,500km of high pressure transmission pipelines and almost 5,000km of distribution networks throughout the North Island, or being turned into LPG and put into bottles (which is what customers in the South Island generally use).

A big chunk of the total gas supply is used to generate electricity and, in 2024, that accounted for around one third of the total. There are two major gas plants - one in Stratford and one in Huntly - and some smaller plants. These can be turned on quite quickly (unlike coal generation) when demand for electricity is high. In a normal year gas makes up most of the non-renewable electricity that’s generated (around 15% of the total).

One company, Methanex, has historically used between 25% and 40% of the country’s total gas supply (it uses it as an ingredient to produce methanol and also as an energy source).

Many big industrial users that require very high temperatures (like fertiliser manufacturing or metal recycling) also rely on gas and that makes up around one third of the total.

The rest - around 10% - is used by residential and commercial customers.

What's been happening recently?

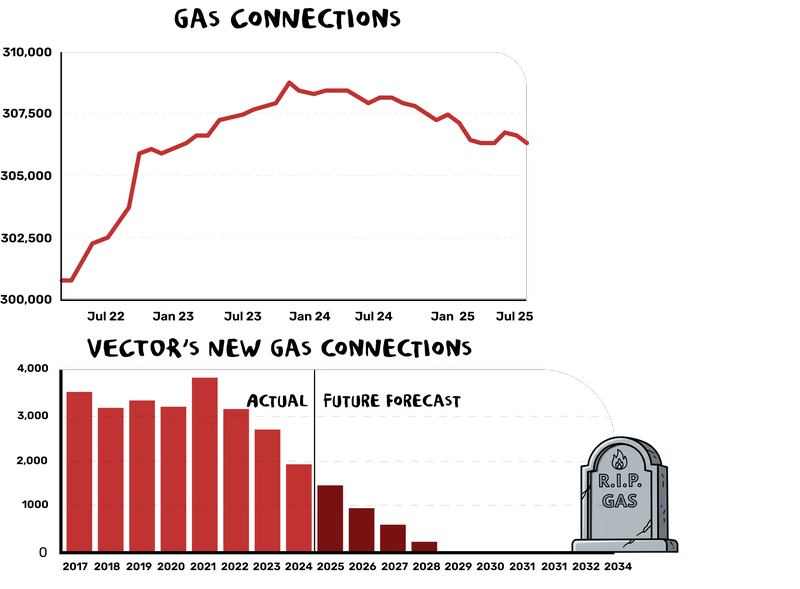

Basically, projections of how much gas we have left in our existing reserves have proven to be too high. According to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), gas reserves were 27% lower as of January 2025 than the year before and they “continue to reduce faster and sooner than previously forecast”. All but three wells are producing less than expected.

The Gas Industry Company, which regulates the gas sector, thinks MBIE is overly optimistic and its projections are even lower.

“The significantly reduced production shown by the orange line is due to production persistently not meeting the expected output. This highlights faster than expected rate of reserves decline.”

Across 2024, total gas production dropped by about 20% and hit its lowest level since 2011. In 2024, our hydro lakes were low, there wasn’t much wind and the gas shortage meant the price was high. People called it ‘a perfect storm’ and, like all of our past dry years, wholesale electricity prices rose to way above the 'normal' level for a few weeks.

To preserve water in our hydro lakes, we typically resort to more expensive alternatives like gas, coal, and even diesel generation at the Whirinaki plant. This sets the price for the rest of the electricity market and has high emissions. Methanex sold a big chunk of its natural gas allocation to the electricity generators, which used about the same amount as the previous year. While that meant Methanex had to reduce its output significantly, it was paid handsomely.

This year, as part of the Budget, the coalition Government put $200 million on the line to underwrite more oil and gas exploration and recently repealed the ban that was put in place by the previous Government.

Will we find any more gas?

Efforts to find gas before the exploration ban was put in place were not very successful and, as RNZ reported, “global investment in speculative drilling for oil and gas has been declining since 2014” and “even before 2018, most of the major oil companies had given up their exploration permits and left New Zealand”. Few believe the recent law change will attract more investment here.

John Kidd, a director and head of research at Enerlytica, frequently quotes the statistic that over the past five years, $1b has been spent drilling 50 new gas wells and they have come up with nothing. The main issue is that one of the first gas fields ever discovered in New Zealand - Maui - was, at the time, the sixth largest gas field in the world, and ever since New Zealand has thought that it was a gas-rich country. Evidence would suggest that Maui was a stroke of luck.

The previous Government used the potential of a large gas field off Canterbury as a reason for the ban, and while there were discussions about ‘peak oil’, the US is now producing more than ever through new technologies like fracking. As Lloyd Christmas might say:

Even if more gas is discovered, it takes many years before a find is turned into a product that can be used and by then it may be too late to stop businesses leaving. The opposition says it will put the ban back in place if it gets back into power, so there is a fair bit of uncertainty that may stop them from trying.

We need a reliable electricity supply in a modern economy and gas still plays a role there as more renewables are built, but we need cheap electricity to unlock all the economic benefits of electrification, and we won’t get that by using increasingly expensive fuels to create it.

What has all this uncertainty meant for big businesses?

For some industries that rely on high temperature heat, gas is still needed because there are few (or no) viable replacements for it in certain products and processes. That means they are much more sensitive to cost increases than households (e.g. if it's just a gas hob that doesn’t make up a huge chunk of the overall bill).

Fertiliser company Ballance uses natural gas as both feedstock and for high temperature heat required to make hydrogen for its nitrogen-based fertilisers. Like Methanex, it recently decided to shut down temporarily (it was effectively outbid for the gas by the electricity industry).

For many indoor vegetable growers, gas is the primary energy source to create heat and many of them also use the CO2 from combustion to increase production. And gas is also used in everything from glass manufacturing to the meat and dairy industry.

RNZ reported that “a survey of business gas consumers by the BusinessNZ Energy Council and Optima found that gas prices have risen by over 100 percent on average over the past five years, with half of the respondents having increased prices, or cut staff as a result”.

In the 2025 March quarter (after adjusting for inflation), the commercial gas price was up 20%, industrial up 15%, and wholesale up 13%, from the same time last year. The gas industry won’t offer price forecasts, but, given the shortage, it’s likely to keep going up and businesses closing or reducing output in part due to high energy costs is leading some to say New Zealand is in the process of ‘deindustrialisation’.

Simon Watson, General Manager of NZ Hothouse, told RNZ some growers are not getting gas contracts at all and others are looking at prices three times what they’re currently paying, largely because the generators are using more of the limited supply for electricity.

This is a big reason why many industrial users are making plans to move away from gas if they can and investing in new replacement technologies like biomass (dried woodchips), electrode boilers or high temperature heat pumps. Watson said he was contemplating moving the business closer to geothermal energy sources in the central North Island.

Some businesses have suggested that the electricity price is too high to switch or that they don’t have the capital to invest in upgrades to electricity connections and new equipment, but businesses like Hayes Metals, which runs a 1.3MVA electric smelter and uses electric induction furnaces, and Van Lier Nurseries have moved early and EECA has given many grants to help businesses transition.

Fonterra's line is that if a boiler still has life left in it, it will re-fire with biomass. If it is at the end of life and needs replacing anyway, an electrode boiler is more economic. Fonterra was getting a sweetheart retail price deal from Meridian (8-10c/kWh, not including network charges), so we saw a lot of economic electrode boilers in the South Island (and the South Island is dominated by coal for process heat because there is no natural gas network).

Not having enough gas to run your business is obviously an existential risk. And the uncertainty around future prices is also a major risk when it comes to investment decisions. EECA’s Regional Energy Transition Accelerator report said gas prices were rising and were also increasingly volatile and this made process heat electrification projects economical earlier.

What's happening with homes and small businesses?

Rewiring Aotearoa CEO Mike Casey has put it in words most can understand: gas in homes is dumb. It’s bad for the bank balance (residential gas prices have gone up by around 20% in the past year), it’s bad for the environment, and it’s bad for our health.

Around 300,000 homes and businesses have connections to the gas network (and it’s estimated another 300,000 use bottled gas). The number of connections has started to plateau recently, declined last year for the first time since data collection began and is expected to keep falling as people disconnect.

The country’s largest gas network, Vector, is forecasting no new residential connections after 2028 and the remaining connections between now and then are typically larger housing developments that received consents to install gas prior to beginning the build cycle and are now coming up to completion.

The chart below plots the change in the number of gas connections on the Vector network (versus three months earlier) compared to the code of compliance certificates (CCCs) issued by Auckland Council. CCCs are a good indicator of completed buildings and better than consents.

.png)

While the rate of completed buildings has slowed a bit in the last six months, it is still at or above the long term average (of the chart range) of 1,000 CCCs per month. In comparison, the number of gas ICPs has dropped off a cliff and started to contract.

We have seen examples where households permanently disconnecting from the gas network have been charged between $1,000 and $2,000 to have a meter permanently removed. RNZ reported a case where a business customer was quoted $7,500 but took the case to Utilities Disputes, where complaints about disconnection costs have been rising.

While gas networks may just be passing on the costs, there’s currently no option for customers to shop around for lower cost permanent gas disconnection services, like you would with other household improvements. Customers have to use the disconnection service provided by the gas network.

In some cases, retailers have said they will continue charging fixed daily fees even after customers have fully electrified, until the meter is physically taken out. These costs are a major barrier to going fully electric, particularly for low-income households, and often come as an unexpected expense. This is especially unfair when the gas connection predates the current owner. Importantly, the gas meter is not owned by the homeowner and may even sit off their property.

The number of gas retailers is also shrinking. Those that remain often only sell gas as part of a dual-fuel package, meaning consumers must also purchase electricity. Only six retailers supply gas: Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Mercury, Pulse Energy, Nova Energy and Megatel (with Megatel a subsidiary of Nova Energy).

Currently only Nova Energy and Megatel are offering gas as an independent product - all other retailers are only offering it as a combo with electricity. This limits consumer choice and deprives gas households of the innovative, lower-cost options increasingly available to electricity-only customers.

Gas households also face two daily fixed charges - one for electricity and another for gas - while electricity-only households pay just one. With the phase-out of the low fixed charge for electricity, the double daily fixed cost for gas connections has become more pronounced (because gas households benefited from being low electricity users).

- Gas customers typically pay around $2 per day in fixed charges (but we have seen examples of $1 to $4 daily charges), or about $730 per year, regardless of how much or little gas they use.

- By comparison, electricity low-user households now pay about $1.50 per day ($548 per year), up from just 30 cents per day ($110 per year) before April 2022.

- In one case study, a household with only a gas hob paid $28 per month in fixed charges but just $6 for actual gas use, meaning around 80% of their charges for gas was just to be connected. The gas hob accounted for 11% of their total energy bill.

With gas network costs likely to rise, these fixed daily costs make gas increasingly uneconomic compared with electricity.

Why focus on getting smaller users off gas?

The gas industry often uses the fact that residential is such a small part of the overall supply to suggest we don’t need to worry about it, but cheaper, cleaner and healthier substitutions exist right now and we believe the Government should help people upgrade to electric options (more on that later).

The majority of homes (and many businesses) in New Zealand can save money from day one by swapping gas space and water heating for financed electric options. This is because the savings from no longer paying gas bills and daily charges are higher than the cost of electricity and finance repayments for new electric appliances.

The New Zealand Green Building Council recently released a report showing that a heat pump conversion programme for commercial and residential space and water heating over the coming decade could reduce natural gas and LPG use by between 14%-38% of current production. Because these machines are so much more efficient than existing electric resistance hot water systems, it would also significantly reduce the need for gas-fired electricity. This would help free up supply for the industrial uses where alternatives are less viable.

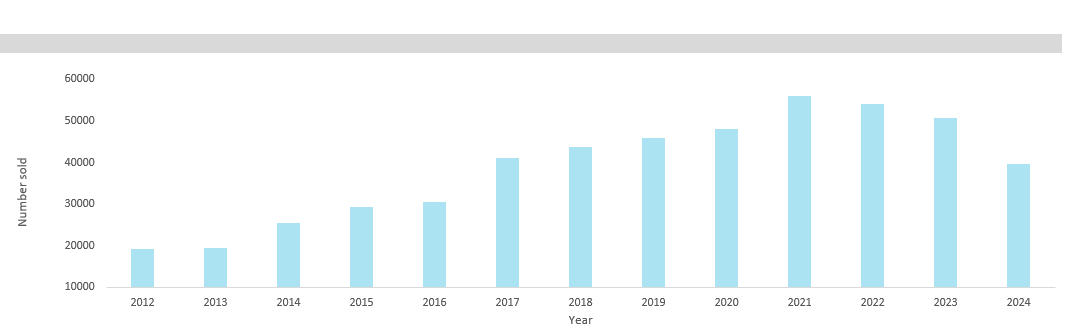

Water heating accounts for around 30% of an average home’s energy use (if you don’t include the energy used in cars, which is by far the biggest chunk). EECA data shows sales of gas hot water systems are on their way down.

Heating accounts for another 30% of total energy in the home and while EECA data doesn’t track gas heating, heat pump sales have been steadily rising.

Sales of both have dipped over the past two years and that is thought to be linked to the economic and construction slowdown, but the decline in the number of gas connections and dire predictions from gas networks would suggest the gas options have peaked, whereas electric options are likely to bounce back when economic conditions improve.

Cooking uses a relatively small amount of energy in the average home, but when the cooktop is the last gas appliance and it’s connected to the reticulated network, these homes will also be paying a fairly high daily charge, so it makes sense to switch to avoid that.

Induction cooking is increasingly being recognised as a superior option at home and some commercial kitchens are also embracing it. Those who install induction cooktops tend to find that it offers better performance and improves conditions for workers. In New Zealand, East restaurant recently upgraded to an induction wok and is now in the process of swapping all its gas hobs because it’s worked so well.

Plenty of reports (like this one) have shown the dangers of burning gas inside the home when it comes to cancer risk. Some of the toxins - like dangerous carbon monoxide from incomplete combustion or hydrogen sulfide - are also heavier than air, so if you’ve got young kids or pets crawling around on the floor, they are more likely to be sucking them up. It is also a leading cause of respiratory illness, so you’re basically paying extra to get asthma.

So, what could replace gas for electricity generation?

Donald Trump has lamented “ugly”, “bird-killing” wind turbines and his administration has threatened to pull out of the IEA if it doesn’t align with its fossil fuel-focused energy security objectives. Closer to home, Resources Minister Shane Jones and Energy Minister Simon Watts have said that we need more thermal generation (i.e. burning stuff to make electricity rather than relying on solar/wind/hydro) because we can’t rely on the weather.

Despite ongoing talk about closing Huntly over the years, the four major gentailers (companies that generate and sell electricity) have recently come together to buy a big bunch of coal that is intended to be used in an energy shortage, otherwise known as a ‘strategic reserve’.

This is largely a response to the faster than expected decrease in gas supplies. There was about double the amount of coal fired generation in 2024 than 2023 to provide more supply during the dry year.

Genesis has also proposed building a new gas plant at Huntly that would be operational from 2027 and there have been whispers of the Government taking over Huntly’s thermal generation and letting the generators compete only on renewables.

While burning coal is not ideal, at this stage it’s probably necessary. It would be an economic (and possibly public health) disaster if the country had rolling blackouts due to a lack of electricity supply and no energy minister would want to get to that point, especially given there is an election next year just after winter. That means we will still need some gas or coal in the short-term for electricity as more renewable generation is built.

The country’s electricity use is expected to roughly double by 2050 (some believe it will increase by much more than that) and the major generators have said that the faster than expected decline in gas supplies has sped up their plans for renewable investment.

Others believe the market is set up to reward scarcity of supply and the gentailers (and their shareholders) make more money when they burn gas and coal. Critics believe the gentailers have been slow to invest their profits in new generation and quick to hand out dividends instead.

If you speak to the incumbents in New Zealand, many of them will tell you there is no way to solve the problem and that more analysis is needed. Could it be because the problem is right now generating a lot of their profits? Lines companies get guaranteed returns on their investments into new poles and wires, so they are incentivised to build them, and generators benefit from high wholesale electricity prices and lose sales volume to households with rooftop solar, so they have a strong incentive to keep things as they are (and tell the three little pigs not to build their house out of bricks). Asking them what they think is like asking the fox to guard the henhouse.

Solar is playing an increasingly important role in electricity generation in many places around the world and it’s largely been at the expense of gas and coal. Solar recently took over from gas in California; Australia has led the world on solar and it too has overtaken gas; everybody loves the wind and sun in Germany - even though it’s not particularly sunny there - and it is helping to get them off Russian gas; Old Brighty took top spot in the EU for the first time ever this month; China is going like the clappers; and even Texas, a huge oil producing state, is now one of America’s biggest solar producers.

This solar revolution is happening at both a small scale on rooftops and balconies and on a large scale at solar farms and it’s being driven by economics.

Jones has said that net zero is a nice idea but can’t come at the expense of hollowing out our economy, but an abundance of cheap electricity could offer a solution to the deindustrialisation he is so concerned about. He has advocated for more geothermal electricity, which has continued to grow as a share of the total energy supply as fossil fuels have dropped, and the Government has committed a total of $82 million (including $10 million from the Endeavour Fund) to explore the potential of supercritical geothermal further down below.

South Australia, which has one of the most renewable grids in the world, is attracting significant industrial interest in its cheap, low-emissions electricity, much of it due to solar, which is helping to keep the price low in the middle of the day.

Rooftop solar, the cheapest form of delivered electricity New Zealand households can get, has often been overlooked in New Zealand. One of our previous explainers explained why solar makes sense and, from an energy system perspective, one big reason is that it can basically turn sunlight into water and help keep our hydro lakes full.

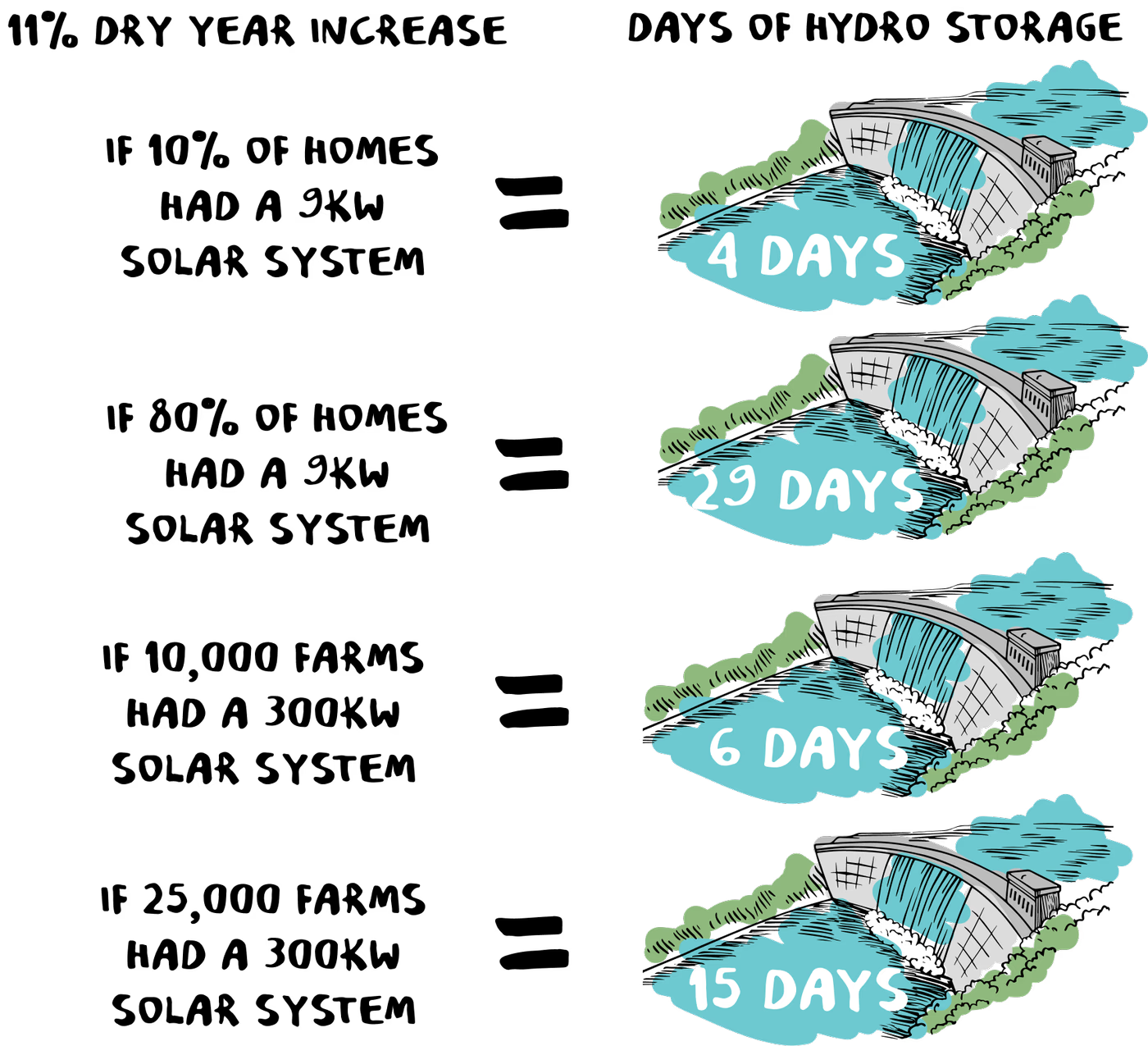

This is even more important during a dry year. You may have noticed that when it’s not raining, the sun is generally out. As our modelling showed, just looking at the extra 11% bump in solar production during a dry year, 50,000 homes and 30,000 farms with solar could equate to 18 days of extra hydro storage, which would have significantly reduced the need for fossil fuel generation and slashed the wholesale price of electricity in 2024.

Rooftop solar adoption rates here have been much slower than other markets, but it is growing rapidly. It’s actually going at a similar rate to Australia around ten years ago, and that’s without the subsidies it had, and the total capacity is now already bigger than all but two of the biggest power stations in the country at 676 MW.

Our current rooftop solar generates around 829 - 1007 GWh each year. This is about 2% of the national electricity supply.

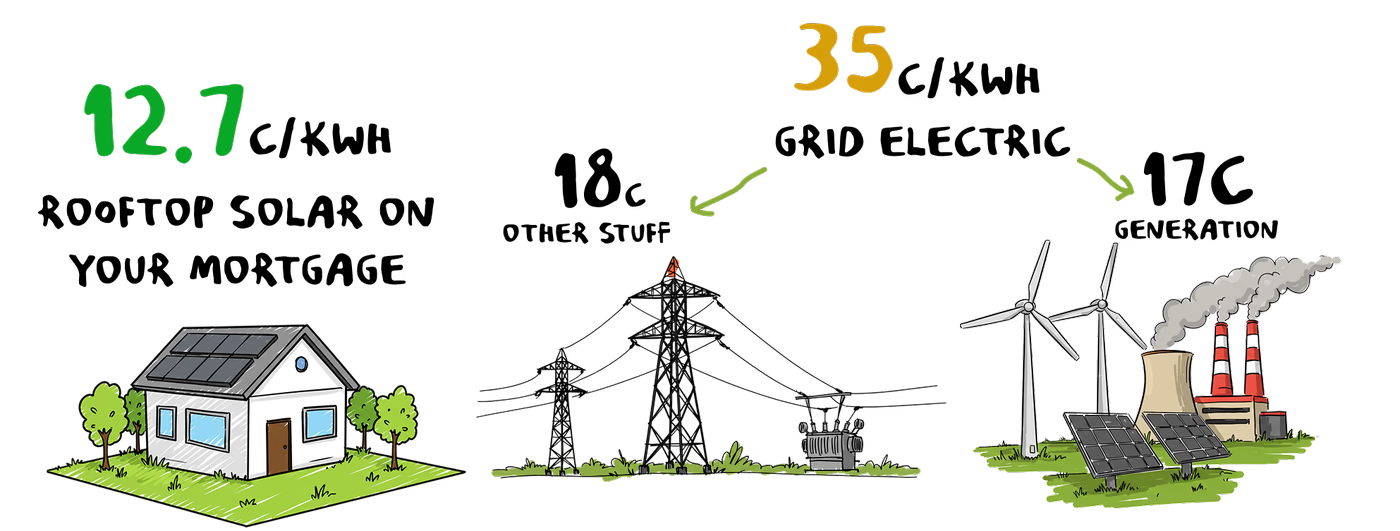

Large-scale solar is also growing rapidly, and that’s a good thing, but it also comes at a higher cost because generation only makes up around half the price customers pay.

If we use our hydro lakes more strategically and keep them full by using more solar, we may only need fossil fuels in an emergency. As electricity demand increases outside of winter (areas like Canterbury use more electricity in summer due to irrigation needs and air conditioning is becoming more common as temperatures rise), solar is also important for this -and to maintain water levels in our lakes ahead of the colder months.

We'll still expect to see loads of solar coming online even with really low summer electricity prices, as we’ve seen in Australia. And this extra seasonal supply can also provide opportunities for flexible demand (like data centres) from very low cost generation.

What about batteries?

Batteries, which have rapidly reduced in price, are also changing the calculations. Fossil fuels are more likely to be used at peak times and batteries basically remove their owners from peak and could potentially remove their neighbours from peak, too. Grid scale batteries could reduce the need to fire up more generation when it’s dark by storing cheaper wind and solar but, like grid-scale solar, it will come at a higher cost to customers.

According to EA data, there are around 80MW of distributed batteries in the country at the moment and this likely understates the true number, as EDBs were not required to backdate the information disclosure when the new requirements came into force in 2023.

For context, 80MW is about the same capacity as Mercury's Aratiatia and Atiamuri hydro stations on the Waikato river, or their $480M Ngatamariki geothermal power station. At the current rate of growth (40MW per year), distributed batteries will reach 280MW by 2030, which will make Kiwi household and business batteries the 11th largest power station in New Zealand by capacity.

Of course, with battery prices coming down, there is every chance the rate of installation and/or the average size of battery (currently 7kWh) will increase. And, as we’ve seen in Australia, where over 1,000 batteries are being installed every day, five times the rate of 2024, incentives can increase uptake and system size considerably.

Just 120,000 homes (or five percent of New Zealand households) with a medium-sized battery could potentially reduce the peak load as much as our largest hydro power station, Manapouri. While these batteries would not hold as much energy as Manapouri, they could output the same amount of power for an hour or two when the system really needs it.

Can’t we use bio-gas or hydrogen instead?

Those with an interest in preserving gas use often point to so-called renewable biogas as a solution. Turning waste into energy is a good idea in theory, and Waste Management New Zealand has a clever programme to turn waste into gas that can then power their electric rubbish trucks. There is also potential with wastewater treatment plants and on dairy farms, but it is even more expensive than fossil gas and there's also nowhere near enough of it to match demand.

Even if all sources of biogas in Auckland were activated, this would only meet around 4% of the network’s current demand.

A story on RNZ outlined how Clarus had to remove an ad that said 'renewable gas was now flowing' following complaints to the Advertising Standards Authority about misleading consumers. The issue was that the ‘renewable’ gas was being blended with fossil gas and only made up a small fraction of the total.

As the story said: "A Gas Transition Plan issues paper written by energy officials said biomethane blending could provide a low-emissions option and boost supply for consumers who were willing to pay a premium in order to continue using pipeline gas, but concluded it was unlikely to win out in the long-term over the cheaper option of electrification."

While there have been recent trials mixing hydrogen with gas, it is very unlikely to be a sensible, safe or affordable substitute for homes, although it may be useful for some industrial uses. There is likely to be a huge cost to upgrade our entire existing gas network to supply hydrogen and that would be a complete waste of money (the phrase ‘hydrogen-ready’ has been used by the gas industry, but as one commentator likes to point out, his driveway is also ‘Ferrari-ready’).

Hydrogen is more like a battery, rather than an energy source. The issue is that it's not a very good battery. You start with electricity, you make hydrogen, you then use that hydrogen to make electricity again. Around one third of the energy you put in comes back out. This is not efficient and it also means hydrogen will be considerably more expensive than electricity for the customer. It’s better to just use the electricity in an electric machine or store it in a battery, if you can.

What about emissions?

Burning gas creates unnecessary emissions that are definitely not compatible with any of our climate targets. Those targets are written into law and a recent ruling from the International Court of Justice suggests countries could be liable for not trying hard enough to reduce them.

The electricity sector accounted for around 4% of our total emissions in 2023, while industrial processes and product use accounted for around 5%.

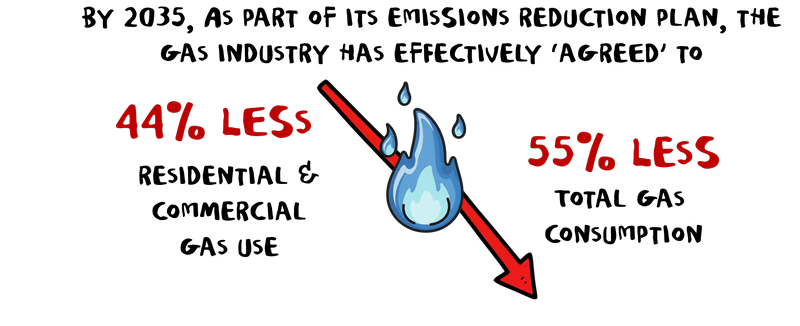

The Gas Industry Company has agreed with its members to adopt a future demand curve for gas that aligns with the Climate Change Commission’s (CCC’s) Demonstration Path from their 2021 advice to the government. The voluntary decision to adopt this curve means that the gas industry is effectively ‘agreeing’ that there will be:

- a 55% reduction in total gas consumption (including as a feedstock) by 2035.

- a 44% reduction in residential and commercial use of gas by 2035.

The majority of the 55% total reduction is assumed by the CCC and GIC to come from reduction in the use of gas for electricity generation, and some major reductions in industrial/chemical use.

The residential/commercial reduction would require around 132,000 connections to cease using gas between now and 2035. That’s a net reduction of around 1,000 connections every month.

In 2021, the CCC did advise the Government to implement a ban on new gas connections from 2025. That hasn’t been implemented, but demand is dropping anyway and, as shown above, total connections have fallen for the first time since data collection began.

What does the future look like?

There are clear indications that new residential gas connections have peaked and are declining and the combination of high exit costs, shrinking competition and rising fixed charges is creating a classic ‘death spiral.’

This trend will be most prevalent among wealthier households that can afford to switch to electric alternatives. There is a danger that those who remain on the network will be disproportionately low-income households, renters, and older people who cannot afford the upfront costs of electrifying and will be left exposed to rising costs they cannot avoid.

Many countries are realising that they shouldn't be sleepwalking into this death spiral or waiting for these networks to close because that will cause absolute chaos.

Some players in the gas industry in New Zealand are asking for electricity customers to subsidise the costs of paying down some of the debt still owed on network infrastructure. But, as Saul Griffith said in The Wires that Bind: “We paid the gas industry lots of money to create this carbon dioxide problem. We shouldn’t have to pay them to stop.”

A report by Castalia for the energy sector suggests that it could cost New Zealand households and businesses more than $7 billion in energy costs and upgrades by 2035 if gas machines need to be converted to electric.

Vector, the biggest gas network in the country, is working towards shutting its gas network by 2050 and says its gas network will potentially be cash flow negative by 2042.

The Canadian government offers a range of subsidies to swap from oil to electricity and has also offered a zero interest greener home loan for upgrades.

Australia, one of the world's largest fossil gas exporters, knows gas has no future in its homes and is doing what it can to manage that transition to electric equivalents in an orderly fashion.

In Victoria, the Gas Substitution Framework is phasing out new gas connections and gas connection requests halved in the first quarter of 2025, and in New South Wales, gas disconnection fees are being capped, with those costs being shared around remaining customers.

Esperance, in Western Australia, is an example of a forced and rushed transition that was more expensive than it needed to be. The entire town managed to move off its reticulated gas network in just 12 months. This transition, involving approximately 400 residents and businesses, was prompted by the gas distribution company’s decision to cease offering the gas service due to commercial unviability.

Horizon Power, the state-owned utility, managed the transition with a $10.5 million government-funded programme. The initiative offered financial assistance to customers to replace gas appliances with electric alternatives, including installation costs and electrical work.

Personalised consultations, educational events and targeted resources were offered to residents and 75% of homes opted to fully transition to electric appliances (with the others using bottled gas for specific industrial needs).

The project is expected to result in average household energy savings of 38% and a significant reduction in Esperance’s carbon emissions.

This example highlights the importance of a proactive, well managed gas transition that looks region by region at when it would be best to retire the parts of the local gas distribution networks, and provides support for customers to make the switch (especially low income and rental households and hard to decarbonise industries).

In New Zealand, the incentives are sparse. There are grants for heat pumps available to low-income homes through the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme, although this is not directly targeting replacement of fossil fuels, and there are promising discussions about the roll out of low-interest long-term loans for electric upgrades through the proposed Ratepayer Assistance Scheme. Upfront costs remain the biggest barrier and we believe access to finance will unlock a lot of demand.

Support for businesses is still available through EECA, but its funding has been reduced significantly, and there has been talk of rationing gas supplies.

If gas supplies continue to dwindle and no new supplies are found, the price will continue to rise to unsustainable levels. Industrial users and commercial operators will stop operating here, or be forced to move their factories and change their energy source. Gas supplies may be occasionally shut off. Gas networks will shut down because they are unviable. And homeowners and businesses may have to rip out appliances and machinery at great expense and without time to plan ahead.

What about all the jobs in the gas industry?

Energy Resources Aotearoa, a lobby group for the fossil fuel industry, estimates there are 11,000 people employed in the gas industry and many are rightly concerned about the loss of jobs, especially in Taranaki.

In Esperance, local tradespeople played a crucial role, with 88% of the work going to local trades. This approach not only supported the local economy but also ensured smooth installations and customer satisfaction.

There will be a huge number of jobs created through electrification, from solar installers to electricians to new businesses spotting gaps and innovating. There are training schemes for gas fitters to retrain as heat pump installers overseas and programmes in Australia for solar installers that don’t require full certification, but very little in the way of industry readiness programmes in New Zealand.

Just as we need the Government and industry to think hard about how to transition homes and businesses off gas, it’s also important to think about how to prepare workers for this transition.

So, what’s the best way forward?

Rewiring Aotearoa’s view is that the Government should support a managed transition away from gas for the homes and non-industrial businesses connected to reticulated gas distribution networks. This would help address inequity for households on low incomes and renters, and provide greater certainty over how quickly customers will disconnect, when networks would likely retire and cost recovery timelines.

It is clear that keeping households on gas is not improving the cost of living, which this Government has been campaigning on.

To prevent worsening inequities, urgent action is required. We believe we need:

- A national gas transition strategy to manage the phase-down of residential and some businesses gas use.

- Targeted financial assistance to help low-income households cover disconnection and transition costs.

- Discourage new residential and some commercial gas connections to avoid gas unnecessarily going to users who have economic alternatives and locking in future costs.

- Explore transitional regulatory models - update gas regulation to be fit for declining supply, take a balanced and equitable approach to gas network cost recovery drawing on the gas transition strategy to provide greater certainty over gas consumption, staged regional gas distribution network retirement and managed decommissioning.

We need an energy strategy that is actually strategic, rather than ‘fuel agnostic’. You can't have a strategy that is fuel agnostic, because if it's agnostic, it's not strategic.

We were not agnostic to Morse code when rolling out fibre internet. We were not agnostic to black and white TV when colour TV was an option. We were not agnostic to the fax machine when mobile phones arrived.

Being fuel agnostic ignores economics because some fuels are far more expensive than others. Being fuel agnostic ignores physics because some fuels operate far less efficiently than others. Being fuel agnostic ignores the reality that some fuels create emissions and New Zealand, along with the rest of the world, has committed to removing those emissions.

We need gas in the short term, but our energy strategy needs to focus on lowering bills, lowering emissions, increasing resilience and ensuring energy security. Gas cannot tick all those boxes because it is expensive (and it's most expensive in bottled form), it is likely to get more expensive (and the options for suppliers are becoming more limited) and it is running out domestically (and it's running out faster than expected).

New technologies arrive and while old technologies rarely disappear, they do lose relevance. Gas is in the process of becoming an old, expensive and inefficient technology. And there are other energy technologies that allow us to use our existing resources in a better way.